Terezín: music from a Nazi ghetto

The Terezín ghetto near Prague was home to a remarkable array of renowned Czech musicians, composers and theatrical artists, writing and performing as they and their fellow Jewish inmates awaited an unknown fate in Auschwitz. Ahead of a London concert to commemorate their lives and work, Ed Vulliamy talks to some of the survivors who remembered them.

Ed Vulliamy, The Guardian, Sat 12 Jun 2010 19.05 EDT

Holocaust survivor Alice Herz Sommer plays Chopin and speaks of how music helped maintain a sense of hope and humanity in the Nazi ghetto of Terezín guardian.co.uk

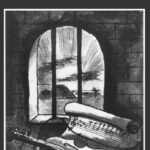

The drawing shows a performance by a string trio, to a small audience. A suited man rests his head on one hand, his left elbow on the arm of his chair; he wears an inward stare of meditative immersion in the music. Next to him, a little girl sits on a low chair, feet tucked in beneath her. A couple are seen from the rear, sitting on a bench, the man’s arm around his lady’s shoulder. The musicians’ faces are hidden, but nevertheless, something in this picture communicates the poignant beauty of whatever they are playing, along with their audience’s rapt attention. The clue to what sets this scene apart from the idyll it appears to be is that the suited man has the star of David sewn on his jacket. The people gathered for this intimate private concert are living in the ghetto of Terezín, or Theresienstadt, as their German captors called it; a former 18th-century garrison town in northern Bohemia, just north of Prague, which was commandeered by the SS in 1940 and transformed into a transit hub for the extermination camps, usually Auschwitz. This is music performed in the antechamber of genocide, soundtrack to the Shoah, as it happened.

The image was drawn and coloured in watercolour by the hand – now wrinkled, but delicate and steady still – of Helga Weissová-Hošková. Now 82, Mrs Weissová-Hošková was 12 when she did this drawing. “Maybe those two are myself and my father,” she says of the figures on the left, with that charged, elegant detachment with which so many Holocaust survivors communicate. She lets on that “I didn’t know how to draw a violin, so I hid the instruments behind the music stands”.

All Nazi camps were diabolical, but Terezín was singular in ways both redemptive, at first, and later grotesque. It was the place in which Jews of Czechoslovakia were concentrated, especially the intelligentsia and prominent artistic figures, and, in time, members of the Jewish cultural elites from across Europe, prior to transportation to the gas chambers.

And as a result – despite the everyday regime, rampant fatal disease, malnutrition, paltry rations, cramped conditions and the death of 32,000 people even before the “transports” to Auschwitz – Terezín was hallmarked also by a thriving cultural life: painting and drawing, theatre and cabarets, lectures and schooling, and, above all, great music. Among the inmates was a star pupil of Leoš Janáček; another was one of the most promising composers from the circle of Arnold Schoenberg. “Many of us came from musical families, and there were very great musicians among us,” recalls Mrs Weissová-Hošková. “Each person was allowed 50 kilos of luggage and many of them smuggled in musical instruments, even though it had been forbidden for Jews to own them. So no wonder the beauty of music and art bloomed in that real-life hell. My father told me,” she says, “that whatever happens, we must remain human, so that we do not die like cattle. And I think that the will to create was an expression of the will to live, and survive, as human beings.”

Perhaps this is why Terezín has commanded surprisingly little attention compared with the infamous extermination camps: it is a complex story of dichotomies, a ghetto camp of which survivors have curiously happy – as well as nightmarish and painful – memories; Terezín was a place of resilience and art in defiance of death, and does not fit in to any simplistic narrative of the Third Reich or Holocaust.

At first, after the ghetto was established and the first “transports” arrived on the 90-minute train journey from Prague, in November 1941, Terezín’s cultural life sprang from the irrepressibility of the talent imprisoned there, in remonstrance of – and often in hiding from – the SS, which ran the camp. With time, the concerts, cabarets, plays, schooling and adult lectures came to be tolerated by the Nazis, as a means of pacification; then, around 1943, even encouraged. In 1944, the SS actually “beautified” the horror they had created at Terezín and invited the International Committee of the Red Cross to visit the camp and see a performance of the children’s opera Brundibár, written by one of the camp’s leading prisoner-composers, Hans Krása. A propaganda film was made, entitled The Führer Gives a City to the Jews, featuring the performance.

But the shocking truth behind the film of the production of Brundibár, which was applauded by the Red Cross, is that apart from two, all the children in the cast were sent, soon after the concert and photograph, to the gas ovens of Auschwitz. Out of some 15,000 children who passed through the gates of what is now a beautifully curated memorial in an uncannily lovely town, only 130 survived.

Helga Weissová-Hošková is one of them. “There were four phases in the cultural life of Terezín,” she says. “First, that of great creative resistance; second, that of the Nazi toleration of the cultural life; third, the manipulation of our art by the Nazis; and finally, when it was all over, the mass killing of almost everyone involved.”

Mrs Weissová-Hošková is among the guests at an unprecedented series of events at London’s Wigmore Hall next weekend, at which the ever-pioneering chamber music group the Nash Ensemble will perform music written in Terezín. Weissová-Hošková’s drawings, done with materials stolen from the Nazi propaganda workshops within the camp, will be exhibited. Other survivors will join her to talk about suffering, death, art and the joy of music-making in Terezín. Films will be screened and presented by the director of one of them, Simon Broughton, a leading expert on world music.

Next weekend’s event is a landmark, not just in this year’s cultural calendar, but in the long history of how and why the Holocaust should be forever taught. The views of those participating are articulate and passionate, summed up in a remark by the great aesthetic philosopher Walter Benjamin, who took his own life while a refugee from the Nazis: “Every image of the past that is not recognised by the present as one of its own concerns is one that threatens to disappear irretrievably.” Mrs Weissová-Hošková says: “I tell the story of my life in Terezín and Auschwitz to children, because they know nothing about it, and they must know, so that it does not happen again.”

Simon Broughton hopes that the events will “capture the entire narrative of cultural life in Terezín”, in a comprehensive way which has, perhaps oddly, never hitherto been attempted in Prague, or, for that matter, New York or Berlin – places to which these performances really should proceed after next weekend. The series is the brainchild of the indefatigable Amelia Freedman, who founded the Nash Ensemble in 1964 and was for years director of classical music on London’s South Bank. She describes next weekend as “not an occasion about the Holocaust but about the triumph of the human spirit over adversity. It is a chance to hear the work of composers who would have gone on to achieve heaven knows what had they lived. There are moments in the works when you wonder: ‘Could this composer have become another Shostakovich or Stravinsky?’ If you look at the history of Czech music after the Holocaust, you see something that was in bloom just before the war, but which simply failed to materialise because it was cut down and killed, literally – the composers murdered.”

And there is another point, of extreme urgency: “Some survivors are still with us to tell the story for themselves,” says Freedman. “Of course, we wish them a long life, but the truth is that this will not be possible much longer. Before long, we will live in a time, tragically, when it will be impossible to hear this horrific story, and about this creative resilience, first-hand. With them will die the first-hand accounts of these terrible events, and of the triumphs.”

Helga Weissová-Hošková lives on the fourth floor of a drab but homely apartment block in the working-class Liben district of Prague. Climbing the four flights of concrete stairs that she still negotiates each day, I consider the fact that interviews with survivors of the Shoah, and in her case Auschwitz, are like no other. Charlotte Delbo, a French survivor and one of the greatest writers about life after Auschwitz, wrote a poem which communicates this truth beautifully: “I came back from the dead and believed / this gave me the right / to speak to others / but when I found myself face to face with them I had nothing to say / because I learned over there / that you cannot speak to others.”

There may be no language for Auschwitz and the camps, but there is memory (or what the Holocaust scholar Lawrence Langer calls “the ruins of memory”) and there is survival. Delbo discriminates between two workings of memory among survivors: there is memoire ordinaire, which recalls the “self” of now, according to whom “the person in the camp at Auschwitz is someone else – not me, not the person here facing you”. Then there is memoire profonde, “deep memory” – according to which Auschwitz is not past at all, nor can it ever be. Between the two is a skin, says Delbo, which “deep memory” can sometimes pierce: “The skin covering the memory of Auschwitz is tough,” she writes. “Sometimes, however, it cracks and gives back its contents.” In interviews with Holocaust survivors one does not know personally, there can be no cracking of the skin. When one knows a survivor well, there can be talk of details and feelings at certain moments. Otherwise, these conversations are charged with code, understatement, omission and dignifying, self-protective detachment. When I reach the fourth floor, Mrs Weissová-Hošková stands in the already open doorway. The aura is immediate, her smile warm but wise, her paintings on the wall. “I will, of course, not tell you every detail,” she says, early in our conversation.

“I was surrounded by musicians all my life,” she tells me. “I was the only one who painted.” Her father, Otto Weiss, was a pianist by passion and bank clerk by trade. Her late husband, Jírí Hošek, whom she married after the war (therefore taking the name Hošková), played double bass in the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra: there is a portrait of him on the piano in the apartment, the instrument being now, says Mrs Weissová-Hošková, “just a memory”. A picture of her granddaughter, Dominika Hošková, playing the cello adorns a bookcase. “I was born in this apartment,” says Mrs Weissová-Hošková. “It is not much, there are better places to live, but I belong here, my roots are here.” It was from here that she was taken to Terezín in January 1942, and to here she returned in 1945.

She talks of life leading up to Terezín; she painted a poignant depiction of her father writing a ledger of the family’s possessions for confiscation by the Nazis, while her mother scours the drawers, as decreed after the occupation of 1939 and establishment of the Protectorate of Moravia and Bohemia, under the Third Reich. “It happened slowly and with determination,” says Mrs Weissová-Hošková, who had been born a decade earlier. “One thing after another was forbidden: employees lost their jobs, we were banned from the parks, swimming pools, sports clubs. I was banned from going to school when I was 10. I was always asking my parents, ‘What’s happening?’ and became angry at them if I thought they were trying to hide something, to protect me.” Eventually, the apartment was allocated to a German family, and the Weiss family transported by railway cattle truck to Terezín.

Once in the camp, young Helga Weissova was separated from her father to live in quarters with her mother, and later in a children’s barracks. There she painted a picture of two children adorning a snowman, and smuggled it to her father in the men’s barracks. His reply came in the form of a note: “Draw what you see”. It was an onerous instruction from father to daughter: make a record, use your talent to testify to the Holocaust, the extent of which no one in Terezín knew, even as the transports began, with trains “to the east”, as the prisoners of the ghetto put it.

Her drawings, exhibited next weekend to accompany the music, compel on so many levels. In style, they resemble early work by the masterly war artist Edward Ardizzone: deft lines and colour wash, with an almost comic-like means of vivid narrative, with attention to vernacular detail. “I think I saw things the adults didn’t see,” says Mrs Weissová-Hošková. “I loved to look at the buttons the ladies wore, the hats, the little things.” So that when a party of elderly German Jews arrived to discover that they were not, after all, in the health spa which they had paid the Nazis to visit, Helga drew their fine hats and tailored coats. There are scenes of lice being removed, of washrooms, and even dark lavatory humour: there was no privacy in the filthy latrines, people forever barging through doors that would not lock, so that a lady had to try to keep the door shut while sitting on the toilet.

The child painted disease, gaunt, drawn faces, she painted poignant gift cards: one for her parents’ wedding anniversary and another for the 14th birthday of a girl called Franzi, which shows the two of them together as babies, then as prisoners, and again in some projected future, pushing their babies in prams. Only the final chapter never came to be: Franzi was murdered in Auschwitz. But there is one drawing in the series which Mrs Weissová-Hošková calls “the one”. It shows children pushing a hearse loaded with loaves of bread and on it the word jugendfürsorge – welfare for young people. “The picture encapsulates the wretched life in Terezín,” says Mrs Weissová-Hošková, “and the Nazis’ terrible way with words. Here we have a hearse, the means of transport in Terezín, for reasons of psychological warfare against us: to demonstrate that we were already dead. They were used to transport everything apart from the dead, and instead of being pulled as they should, by horses, the animals were children.” And there is that word: jugendfürsorge. “The welfare of children who would, all of them, perish in Auschwitz.” Mrs Weissová-Hošková’s face stiffens, and her soft voice hardens with the survivor’s polyphonic entwinement of rage, sorrow and contempt. “This was the essence of Terezín.”

Terezín was run, on Nazi orders, by a Council of Jewish Elders, whose task on the high wire of their captive responsibility was to carry out the diktats of the Nazis while making the lives of their own people as bearable as possible. Horrifyingly, it was the council’s duty to make selections for transports to the east, according to quotas the Nazis gave them. They also organised a cultural life, under the auspices of the Freizeitgestaltung (free-time administration), who could draw from the inmates of the camp an enormous – a disproportionate – number of talented musicians, who had managed to smuggle in banned musical instruments (or at least parts of them, for reassembly).

Czech music during the inter-war period of the brief and proudly democratic Czechoslovak republic stood at a crossroads of electrifying creative potential. As part of the Austro-Hungarian empire which collapsed in 1918, Czech music had been subject to two influences epitomised by the glowing dualities in the work of its great ancestor, Antonín Dvořák: the Slavonic folk tradition and the Viennese classical and romantic traditions. At the beginning of the 20th century, the former was driven to new levels of sophistication – and on a bold emotional, psychological, political and chromatic adventure – by Leoš Janáček, to forge a deeply and singularly Czech musical timbre. In Vienna, Schoenberg, Webern, Berg and the expressionist movement had meanwhile embarked on an atonal, modernist revolution. What might have followed in Czechoslovakia as these movements collided and entwined could have become every bit as important as what Shostakovich, Stravinsky and Prokofiev did to Russian music out of the rubble of 1945, had not its authors been taken to Terezín and eventually murdered in Auschwitz.

There were four composers of note in Terezín, and foremost among them was Viktor Ullmann. A great talent from the circle of Schoenberg and his brother-in-law Zemlinsky, Ullmann wrote some of the most important music to be played next weekend, and a masterpiece opera – The Kaiser of Atlantis – which wasn’t actually performed until 1975, in Amsterdam. Often, concerts and compositions in Terezín would express suffering and resistance. “They wrote in codes,” says Simon Broughton, “coded phrases, key codes, Czech folk and Jewish tunes, references to melodies like Smetana’s ‘Má Vlast’ (My Homeland) with specific associations in the minds of the audiences that the Nazis were too stupid to spot.” Not, however, with The Kaiser of Atlantis, which – although it was originally conceived by its leftwing librettist, Peter Kien as an allegory about the evils of capitalism – is pure pastiche of the Third Reich and Adolf Hitler, and even contains a parody of “Deutschland über alles” itself. In the opera, the figure of death refuses to lead a war of glorification for Emperor Uberall, and in the tumult that follows, death only agrees to return to duty if the Kaiser himself is the first to die. The production in Terezín reached dress-rehearsal stage, at which point it was banned by the SS.

Pavel Haas was a star pupil of Janáček and already an established composer when he arrived at the Terezín ghetto in 1941. Haas’s development of the authentic Czech sound, rooted in folk song, reached a peak of creative output in the ghetto, before he was transported to and murdered in Auschwitz. Gideon Klein was another ghetto inmate, influenced by the symbolist movement and poetry of Baudelaire, and his searing, beautiful string trio piece forms part of next weekend’s programme. Alice Herz Sommer, a survivor who played hundreds of piano concerts in Terezín, and who is now living in London, says it may have been intended as a quartet, but that Klein’s second violinist was transported to Auschwitz, as was Klein himself soon after.

Hans Krása was the composer of Brundibár. The children’s opera was first performed at a Prague orphanage run by a keen amateur musician called Moritz Freudenfeld, who at his 50th birthday party, in July 1941, insisted that it be premiered on his premises. By the time of the premiere Krása was in Terezín, soon to be joined by everyone else who was at Freudenfeld’s birthday gathering. Eventually, Brundibár would be performed 55 times in the ghetto – the cast of children perpetually changing, as they were transported to Auschwitz and replaced on stage by others.

Conductor Karel Ančerl was also pivotal to the musical life of the ghetto, He survived not only Terezín but Auschwitz too, and after the war returned to Terezín, where he recovered much of the discarded music written in the ghetto. As musical director of the Czech Philharmonic, Ančerl went on to establish himself as one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century, alongside Furtwängler, Mravinsky, Karajan, Bernstein and Solti (with all the kaleidoscope of political allegiances and narratives evoked by that roll call of genius).

“It’s hard to place what was happening in Terezín within the narrative of the Holocaust,” says Broughton, the anchor of next weekend’s events. “The conditions were appalling, tens of thousands of people died of disease, hunger and malnutrition. Yet it was not an extermination camp; people were free, relatively speaking, inasmuch as what the Germans had prohibited as ‘degenerated art’ across all Europe thrived in Terezín. There was jazz played by a band called the Ghetto Swingers, there were cabarets, there was theatre. Of course, on this occasion at the Wigmore, we’re playing the music firmly from within the ghetto. But it is good music in its own right, sometimes very good – if not always great – music, and deserves to be part of the mainstream repertoire.”

Alice Herz Sommer is sitting in an armchair at her flat in Belsize Park, north London. “Music is mankind’s greatest miracle,” she says. “From the very first note, one is transported into a higher, other world, and that is how it was when we played or listened in the ghetto.” Mrs Herz Sommer is 106 years old, but effervescent with life, and to talk to her is to converse with history itself. “My mother’s family played with young Gustav Mahler,” she will drop casually into conversation, or “Franz Kafka, whom I knew well as a dear friend…”

Mrs Herz Sommer was an accomplished international pianist by the time she arrived in Terezín with her husband and son, in 1943, on one of the last transports from Prague. “The main thing was to protect my son from what was happening,” she recounts. “He would keep asking: ‘What is war? Who is Hitler? Why are we here and hungry?’ And when we came to write a book together, the part which gives me most pleasure is when Raphaël wrote that thanks to his mother, he remembers very little about life in the camp.” Raphaël Sommer grew up to be a pupil of the great French cellist Paul Tortelier and a great cellist himself. Sadly, he died suddenly in 2001.

It was into the musical life of Terezín that 40-year-old Alice threw herself. She accompanied, as a pianist, a famous performance of Verdi’s Requiem. “We were criticised for not doing Handel, or something from the Old Testament,” she recalls, “but so what? We wanted to perform a requiem, and Verdi’s is the greatest.” Was it a requiem for the dead of the ghetto, for the Jews? “Why not?” replies Mrs Herz Sommer.

“I am by nature an optimist,” she continues, her mind as sharp as a scalpel, “but I am pessimistic about future generations’ willingness to remember and care about what happened to the Jews of Europe, and to us in Terezín.” Her optimism is that of the silver lining in the dark cloud: “I think that great art can only come from tribulation and suffering, and that wealth is something of the spirit. Rich people are ridiculous – they think they have everything, but they have nothing!” she laughs. “We who survived the ghetto have our suffering, and the music which lifted us out of suffering, and that makes us richer than any wealthy man.”

Her husband’s cryptic parting words to his wife as he was taken away for “transport” were, she recalls: “Never volunteer for anything.” Alice was unsure what he meant, but obeyed. Sure enough, three days later, many women and children were among those transported, having volunteered to journey “to the east”, in the hope of joining their menfolk. Alice, instead, was among the few who remained in Terezín until the end of the war, playing concerts even after her mentor in the camp, Rafael Shaechter, had also been taken and murdered. He was, she says, “such a motivator, always encouraging us to overcome our surroundings, to sing and play.”

Shaechter had “discovered” young Alice when he heard her give a performance to fellow inmates of Beethoven’s Appassionata piano sonata, which, she says, “I performed more than 50 times in Terezín and hundreds of times since”. When she returned to Prague after the liberation of Terezín, “I sent a telegram to Palestine telling my relatives: ‘Tonight, I will play the Appassionata.‘ That is how I told them I was still alive.”

On 7 February 1945, while the last members of the Freizeitgestaltung were shipped to Auschwitz, she gave a recital, an all-Chopin programme which she repeated several times until 14 April, five days before Hitler, in his bunker, declared to his generals that the war was lost. For the ears of those few remaining in Terezín as the Red Army stormed Berlin, Alice then switched to performances of works by Beethoven and Schubert, including a Beethoven violin sonata for which Alice was accompanied by her brother, Paul Herz. “We made music,” she says, “and of those evenings I have very fond memories.”

“Would you like a cup of tea?” she now asks, on a sunny morning in Belsize Park. Yes, I reply, but please remain seated, madam, I’ll make it. “No, sir!” she retorts. “You remain seated while I make tea,” which she does. And after some hours of discourse, mostly about music rather than the Holocaust, she says suddenly: “Thank you for our conversation. Now I must play. I must begin my playing every day with one hour of Bach. I have come slowly to appreciate German culture. Because of Hitler, obviously. But what could be more wonderful than Bach, Beethoven and Schubert, the greatest of the Romantics? But it all begins with Bach, the philosopher of music.” And she moves, slowly but steadily, to the piano; the sound of the “Well Tempered Clavier” played by a 106-year-old Holocaust survivor drifting out across London NW3.

Fragments of the Nazi propaganda film The Führer Gives a City to the Jews have survived, and they are appalling to watch: a football match, gymnastics, wholesome growing of vegetables in allotments, the production of Brundibár – and happy children playing and eating. “But watch how they eat, the children,” says Helga Weissová-Hošková, her usually calm voice trembling with rage. “Watch how they devour the food. They are made to say: ‘Oh no, not sardines again!’, but watch their eyes, see how they eat the food, and when you watch the film or see the photographs the Nazis took, tell yourself that soon afterwards, when they had fulfilled their purpose for Hitler’s propaganda, those children were all sent on the transports to Auschwitz and murdered.”

Of all the children in a famous photograph of Brundibár‘s cast, only two are known with any certainty to have survived: one was Mrs Herz Sommer’s son, Raphaël; the other is dressed in black, as a cat, next to the main character. Her name is Ela Weissberger and she lives in the United States. “She is a dear, dear friend of mine,” says Mrs Weissová-Hošková, “and she is coming soon to Prague to visit me.”

Mrs Weissová-Hošková’s early work is hallmarked by strong lines and bright colours. But later, it dims into flurries of hurried line, and darker hues. “I literally used a wash of dirty water,” she says, “and there was certainly no shortage of that!” Towards the end of her time in Terezín, in 1944, she drew the arrival of children from Bialystok, Poland, who, diseased and malnourished, were taken to the showers and panicked in fear, shouting “Gas! Gas!” “They knew what we did not know about the east, but had begun to suspect,” says Helga Weissová-Hošková. “They were terrified; they understood.”

After that of the Polish children, there follow two more terrifying pictures in a similar, dark palette: both of the separation of those departing on the transports and those remaining behind, who were forbidden to speak to those “selected”. “We know now what we did not know then what these are pictures of,” says the artist. “They are the moment of final farewell.” Even before her beloved father’s transport to Auschwitz, and later her own, teenaged Helga Weissová was obsessed by these moments, writing in her diary that the “thunderous steps, the roar of the ghetto guards, the banging of doors and hysterical weeping always sound – and foretell – the same”.

On 4 October 1944, Weissova and her mother were transported to Auschwitz, and arrived to face “selection” by none other than Dr Josef Mengele himself, directing arrivals on the platform either left towards the gas chambers or right towards the barracks and forced-labour dispatches. “The rows in front of us are moving,” the 15-year-old Helga wrote in her journal, realising immediately that children were being sent left to the ovens. “It’ll soon be our turn… the rows are quickly disappearing, the five people ahead of us are on their way… just two more people, then it’s us. For God’s sake, what if I’m asked what year I was born? Quick, 1929, and I’m 15, so if I’m 18… ’28, ’27, ’26. Mum is standing in front of the SS man – he sends her to the right. Oh God, let us stay together! ‘Rechts’, the SS man yells at me, and points the direction. Hooray, we’re on the same side.”

Eleven days later, another train from Terezín pulled up in Auschwitz, carrying Hans Krása, Viktor Ullmann, Gideon Klein, Rafael Schaechter and Karel Ančerl, to face the same “selection”. The latter was separated from his wife and child, who were sent to the gas ovens, along with the others, the creative core of Czech music.

“How did you survive?” I ask Mrs Weissová-Hošková. “Is that a question?” she retorts. “There was no way to know. It was sheer luck – or was it providence, or what? This way, left, to the gas chambers. That way, right, to the labour camps and the rest of what then happened to me, that I had to go through. There was no reason or… there is no answer to that question. Who knows why or how anyone survived. As I say in the painting: ‘WHY?'”

Mrs Weissová-Hošková was transferred from Auschwitz to a labour camp that formed part of the complex of Flossenbürg, the only concentration camp which fully carried out Heinrich Himmler’s orders at the very end: to exterminate every single inmate. But Weissová survived a second time: before Himmler issued his order, she was forced on a 16-day “death march” (of which she has drawn terrifying images) to the Mauthausen labour camp, which she endured until liberation, returning then to this very flat in Prague 8, on Kotlaskou Street, in which she was born and still lives.

She points to a painting which she says “I consider my most important of all. It hung a while above the piano, but I took it down.” It shows a pile of children’s shoes, from which ascend plumes of smoke in which eyes are set, asking – no, screaming – “WHY?”

Primo Levi wrote: “Do not think that shoes form a factor of secondary importance in the life of the Lager [concentration camps]. Death begins with the shoes.” The removal of the shoes, before the gas chamber, is a scene recalled in his memoirs by Filip Müller, a member of Auschwitz’s sonderkommando, prisoners commandeered to assist in the death camps. “I was watching a young mother. First she took off her shoes, then the shoes of her small daughter,” Müller wrote. “Then she removed her stockings, then the stockings of her little girl. All the time she endeavoured to answer the child’s questions readily: ‘Mummy, why are we undressing?’ ‘Because we must.'”

Helga Weissová-Hošková turns to another picture of hers. It shows her granddaughter, the cellist Dominika, when she was a baby in a cot, asleep. But underneath the cot lies a pair of little red slippers: “The thing is that, for me,” says Mrs Weissová-Hošková, “I cannot see those slippers of a safe, secure child without thinking of the other shoes. These shoes,” and she turns back to the picture of the shoes and the smoke. We sit for a while in silence, eating the sandwiches she has kindly made: it is mid-afternoon, and summer, but one of those grey days that never really dawns. A drizzle falls, the trams clank outside and music drifts from a distant radio. Before I take my leave, Helga wants to show some last works. One is a painting in which, behind a fallen autumn leaf in what looks like a cracked skull, or egg, a curtain is drawn and spring flowers bloom in a blue sky of redemption, some form of resurrection from the ashes, regeneration from the shattered egg. But then she opens a file of her prints from etchings into lino or wood. Most of them are prints of the same themes as her paintings, but in black and white, and they are like the spine-chilling monochrome of Auschwitz itself.

Walking around Terezín now, one visits a place of colours: a curiously “normal” – albeit haunted – town and carefully arranged monument to both the suffering and the creativity; the grass is green, the sky blue and the wash on the walls of the buildings where Alice Herz Sommer and Helga Weissová-Hošková lived is a burnt sienna ochre. Late prints by Weissová-Hošková recall the place for which Terezín was the transit point for the “transports”. These prints convey that feeling, when one visits Auschwitz, that only they – and no words – can express: Auschwitz, where even the ghosts are dead and the colours silent, and everything seems, like these prints, black and white, metal and snow. Black, spidery watchtowers with slanting roofs and long, black stilts for legs behind the black fencing, attached to black poles, silhouetted against powdery white across the ground. Black and white, but not like in photographs, not even photographs of Auschwitz, where there is penumbra. In Auschwitz (in winter, at least), the black is too black and the white is too white, as they are in Weissová-Hošková’s heart-stopping prints.

“I am still inside,” says Mrs Weissová-Hošková. “Once a prisoner in the camps, you are always inside. In fact, the older you get the more inside you go. Every time we meet, friends who have survived, we talk, we laugh, we joke, we are alive together, we exchange news and talk about music, children, grandchildren, our lives now. But we always return to the same thing. The camps. Terezín, Auschwitz. We always go back inside.”

The Nash Ensemble’s Music in Theresienstadt-Terezín 1941-45 runs next weekend, 19-20 June. For information, visit wigmore-hall.org.uk

Schoenberg & Berg (Barbara Hannigan)

Schoenberg’s soundworld thrills under Gardner

Second Viennese School